Life in a Cage

This piece on cage fighting started out as one thing and ended up as another. I began to put together something on the fighting scene in Australia; then it was announced that the UFC would stage a debut fight-night there: huge news. The UFC pushed for coverage, and so did a videogame company… Soon I had about four million interviewees and could have written a short, dull book. Instead, I forced it down to this, which is all right, considering. The story was for Alpha magazine and the photographer was fight maestro Sam Ruttyn, whose before/ after shots of these guys are amazing._________

It is a dark and stormy night – and there is violence in the air. The rain hits Sydney’s Luna Park dead-on, then side-on. Big blokes in wet T-shirts hurry past the Ferris wheel and the bar; some are with girlfriends; most with mates. They are all here for the cage fighting.

At the Big Top, everyone gets searched and scanned. We queue shivering under the awning while the gale twists across the bare concrete, the closed rides and sideshows, and plucks at our dripping clothes. Inside, it smells funky and close. A girl in a bikini, high heels and hair colour she wasn’t born with sells T-shirts and muscle shirts by the rack. They say “Affliction Rush” or “MMA Factory” or “Tapout”. People pick through them, get beers from the bar or stand in an available space trying to dry off. Two of them, Ian and Brad, tell me they’ve paid $130 each for tickets and would have paid more. Ian and Brad look like pin-up boys for computer programming; they’ve never swung a punch in their lives. They’re just into it. It’s new and exciting and something a bit different. Welcome to ground zero of the fastest-growing sport in the world.

Cage Fighting Championships (CFC) is Australia’s best and only organisation trying to ride the coattails of this international sporting phenomenon, and cater to the Aussies who crave live action: five-minute rounds, using whatever martial art you want; light padded gloves; bare feet; kicks; punches; strangleholds; knees; elbows; skill and blood and drama. And crave it they do.

At about the time this magazine hits shelves, CFC’s very big brother, the American Ultimate Fighting Championships (UFC) is holding its own show at the ACER Arena, Olympic Park, the first occasion big-time cage fighting has come here. The 17,000-seat ACER sold out in eight hours, creating a new indoor record in Australia – 50 per cent of those tickets bought interstate. The UFC set aside money for advertising: it wasn’t needed. The tickets were gone before a single fighter on the card had been named. For an amusing comparison, the Danny Green-Roy Jones boxing match failed to sell out the same arena, despite weeks of advertising and publicity efforts from both fighters.

It wasn’t always this way. The story of cage fighting is a short and mostly sorry one, and its growth is one of those modern events of the internet age, like a Facebook spike, a Twitter plague. Chances are, if you’re over 30, your interest in cage fighting is at one extreme or another – rabid fan, or total ignorance and indifference. And there are very good reasons for that.

It wasn’t always this way. The story of cage fighting is a short and mostly sorry one, and its growth is one of those modern events of the internet age, like a Facebook spike, a Twitter plague. Chances are, if you’re over 30, your interest in cage fighting is at one extreme or another – rabid fan, or total ignorance and indifference. And there are very good reasons for that.

Cage fighting’s reputation is the worst of any sport. Bar none. The very first organised, UFC event, in 1993, was billed as “no holds barred” – a lawless, bloody free-for-all that featured several injuries. It was an interesting mess, with heaps of potential that hardly anyone could see. The trouble is, that’s the reputation that stuck. They’ve since developed and remade the entire sport, made it far safer, more regulated, but you could have made it a tickling contest after that and few would have noticed. Ask the man in the street about cage fighting and he’ll tell you there are no rules; that the blood and gore would make you sick. These people belong in a cage.

In 1999, US Senator John McCain called the sport “human cockfighting” and had it banned from nearly every state in the union. It was thrown off cable television. You can show hard-core porn on cable television. As late as 2003, the sport was less than a blip within a blip. You could have bought the entire sport, with wrapping and a card, for a million bucks. Now, an offer of a billion dollars wouldn’t even get you in the room.

Back at the Big Top, 1500 Aussies watch Tony Ballout and Jade Jordan wrap themselves in a long, intense battle, most of it on the ground. As they move carefully from side-hold to full-hold, looking for arm-bar and submission, it’s hard to believe cage-fighting’s gruesome reputation. The atmosphere is surprisingly quiet and the MC tells everyone to “make some noise”. It feels less like fight night than a session in the gym: a combination of basic testosterone and the application of hard-earned skill. And that’s the key to understanding this sport. Its origins aren’t in the pub or the street or the underground car park. They’re in the dojo.

_________

It didn’t start with a fight, it started with a question. “What would happen if… ?” Perhaps the question had always been there. What would happen if your best guy took on our best guy? Hand to hand – none of that stuff with the sling that David tried on Goliath. Bruce Lee would kick Muhammad Ali’s ass, right? Just shooting the shit. Never happen. Let’s make it happen.

It didn’t start with a fight, it started with a question. “What would happen if… ?” Perhaps the question had always been there. What would happen if your best guy took on our best guy? Hand to hand – none of that stuff with the sling that David tried on Goliath. Bruce Lee would kick Muhammad Ali’s ass, right? Just shooting the shit. Never happen. Let’s make it happen.

The trouble is, the big guys with boxing training kept knocking out the martial artists.

The karate people were rocked. The judo and the kung fu devotees, the Enter The Dragon, would-be Grasshoppers found themselves seriously sidelined by massive blokes from the country who took their fancy moves, then tore their house down. This was early cage fighting. Two wrecking balls, no holds barred, seeing how much damage they could take and still stand up. Martial arts was all very well to keep fit and centre your whatevers, but not so effective in a proper brawl. It would eventually have died or gone underground, but for Royce Gracie.

If there’s a god of cage fighting, it’s Royce Gracie. The Brazilian is part of a fighting family who took Judo and uglied it up. Brought it down to the canvas. Brazilian Jujitsu has a look at all your wild, swinging machismo and tangles it in a web of holds and arm-locks and chokes, until you’re terrified the bastard will snap a joint or tear a ligament or some other horrifying thing. In 1980s California, the Gracies offered a challenge (and mythically $US100,000) to anyone who could beat the slightly built Royce, but nobody could. Royce Gracie won that first Ultimate Fighting Championship in ‘93, and showed that Brazilian Jujitsu gave you options when the gorillas tried to knock your block off. It wasn’t about gore and bravery: it was about tactics and technique. You could move across disciplines to give you options, from boxing to Muay Thai and karate and wrestling and Jujitsu. It took a long time to develop, through the long and painful ‘90s, but, Gracie had shown the way.

Eventually, what it needed was something to give it a real kick into the public consciousness. In 2005, it got The Ultimate Fighter. The reality show, devised and run by UFC’s president Dana White and owners Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, was a proper tournament, featuring 16 fighters and, most importantly, the finale was live on free-to-air television. Viewing figures were high. People caught on.

Growth since has been so quick, there’s still the feeling that fighters can barely believe how good they’ve got it. George St Pierre, a polite and clean-cut French-Canadian, is the UFC’s current welterweight champion. “I was into karate, so my dream was to become a karate or martial arts champion,” he says. The first time I saw UFC I was inspired, but growing up, it was very hard. The sport was not accepted. In Montreal, I was seen as an animal in a cage and lots of people had a misconception of who we are.”

St Pierre told his parents he was giving up university to train full-time, see where he could take it. It’s at the heart of modern cage fighting: not necessarily the need for a fight, but to test yourself, try things out. “The guys who do well are not necessarily from the street. It’s a very technical sport, so you need to be smart, to put things together, and when you fight a guy you need to be able to analyse him and know what his strengths and weaknesses are. You need to have a minimum of logic and apply your own technique. I’m a very good technician.”

Australia’s most-successful UFC fighter has a similar tale to tell. “I’m not an aggressive person,” says Elvis Sinosic. “I did martial arts and I always wondered whether what I did worked. Everyone who trains martial arts must think that. I read about no-holds-barred cage fighting in a magazine and it sounded awesome. I watched videos and what was impressive was seeing technical skill overcome brute strength. You want to test your skills, but also don’t want to end up on the ground getting curb-stomped, on the street.”

Self-managed, Sinosic got his chance at international mixed martial art (MMA) combat in 2000, at the K1 Grand prix in Japan, his narrow loss enough to get him a shot with the invitation-only UFC, even then the loudest noise in the sport. He won his fight inside three minutes. As an Aussie in the UFC, he was alone. Not that he cared. “It was a great experience. I was so in awe. I knew I was one of the first, but I didn’t think of it like that. It was just competing. When you’re standing in the cage across from your opponent, everything else disappears and it’s just that personal challenge.”

Ten years later, Sinosic finds himself such a loved veteran he’s on the UFC’s bill in Sydney, against fellow Aussie star Chris Haseman. It’s a heady situation for the local scene, and one it desperately needs. “We’re about where the UFC was about five years ago.” says Sinosic. “You’d be surprised how many people are starting to discover the sport. It’s growing, but we really need that something extra to kick it over.”

The CFC was started in 2007 by former fighter and trainer Luke Pizutti, who realised that there was plenty of eager local talent but very few shows for them to appear in. “At that time it was hard for someone to become a professional fighter because there just wasn’t the money in it,” he says. “Even now it’s still very hard.” His aim was to get it on TV and then get sponsorship, and the shows gradually improved until Fox started showing it for free in 2008; the American version, of course, you have to pay for.

Pizutti admits he’s still doing it for love. There’s no money here yet. “It’s like every business – you’ve just got to put back into it. The perception is that we are making money out of it, but a lot of our money has gone on production costs, flights and accommodation… We’re just starting to have the budget to advertise. And we’ve got to pick up the pieces from people who put on poor fights. If we’re telling people to come and watch CFC and maybe their first or second exposure was a mismatched fight… We’re under pressure to put on a premium fight. We’re trying to find people all the time who can stand up. And when we give people the opportunity, they know this is the time to put on the best fight ever.”

_________

At Luna Park, Tui Wright, 147kg, not all of it muscle, takes on Penrith’s Lucas Browne, who is 120kg and most of that probably is muscle. You sense this is one of those battles Pizutti doesn’t need, a step down the rungs to Bubba v Butterbean. The faster, leaner Brown pounds away at Wright’s face without meaningful response. Before long, blood sprays across his face, on the canvas. The lumbering Wright is billed as a kickboxer, but I can’t see it. It’s a violent sport, and this is what violence does.

At Luna Park, Tui Wright, 147kg, not all of it muscle, takes on Penrith’s Lucas Browne, who is 120kg and most of that probably is muscle. You sense this is one of those battles Pizutti doesn’t need, a step down the rungs to Bubba v Butterbean. The faster, leaner Brown pounds away at Wright’s face without meaningful response. Before long, blood sprays across his face, on the canvas. The lumbering Wright is billed as a kickboxer, but I can’t see it. It’s a violent sport, and this is what violence does.

Cage fighting fans can be very defensive. Can’t blame them, really. Get the details wrong, or dare to criticise, say, lawn bowls, and no one gets too worked up. But, then, lawn bowls isn’t under attack. No one’s calling it human cockfighting. I’ve talked to fans, fighters, promoters and commentators, and the one constant line is that the public and the media need educating, we don’t get it, we don’t understand… “To get anywhere, you need recognition and you need the fans to understand what’s going on,” says Elvis Sinosic. “Educate the fans and they’ll want to watch it.” “It is a very dangerous sport, it’s true, a contact sport,” says St Pierre. “But it’s not violent. We are fighters – that’s what we train for, it’s our job. I’ve seen an ice-hockey player hit another player with his stick – and that was free violence, you know? If, for instance, I go into a fight and start eye-gouging the guy or head-butting the guy, it’s breaking the rules – it would be free violence.”

And yet. To many it remains an almost-impossible sell. A step too far. For all the skill on show, there is still the whiff of the prison yard or the schoolyard about cage fighting. Despite the rules, it remains one guy beating up another; it can be hard, even for the hardened boxing fan, to accept the sight of one guy sitting astride another, punching him repeatedly in the face. To beat Frank Mir last year, the monstrous heavyweight champion Brock Lesnar pinned Mir on his front and gradually beat him unconscious. It’s odd how society grades its violence: boxers punch harder, set themselves properly without fear of being kicked, and tee-off from their boots – but at least they are on equal terms at all times. It looks, somehow, better. The UFC are trying to sell blood and savagery into your lounge. And they are acutely, painfully aware of it.

The mission for the sport since the terrible mid-‘90s has been to make it safer, yes, but also tame it, brush up that rep, and make it fit for civilisation. The phrase “cage fighting”, like “no holds barred” has been quietly sidelined. It’s a bit raw. Instead, we have vanilla initials like MMA and UFC, while the cage is now an “octagon”.

_________

The press conference to announce UFC 110 in Sydney is the most wondrous thing I have ever seen. The press notes tell me, in detail, about fighter safety and pre-fight medicals; about how very many rules and regulations there are (no no-holds-barred, see?) and on and on, until it gets boring. And then goes through boring into scientific studies of injury trends and the history and nature of injury in all fights…

On the dais are six of the fighters who will appear on the card, some flown over from America. One by one they are introduced and make a short speech saying how proud, excited and privileged they are to be involved. It’s like a school prize-giving. Brazilian Wanderlei Silva, who has dead eyes and a jaw like a corral shelf and is billed as “one of the most aggressive fighters in the sport – a knockout artist” says a few shy, halting words, not one of them about himself. This is where trash talk came to die.

Afterwards, I am granted an interview – straight away, no time limit – with Marshall Zelaznik, the well-spoken New Yorker charged with spreading UFC across the globe. It’s surreal. It’s big-time sport without ego. Imagine that, if you can. UFC’s other mission is to Not Screw Up. Not do what boxing did.

Boxing is MMA’s nearest equivalent and rival. Many of the people who run MMA, including Zelaznik and UFC’s head honcho Dana White, are long-time boxing fans, but are backing away from its miserable carcass as fast as they can.

For the disenchanted fan, boxing means multiple world champions, meaningless fights, overhype, under-deliver, low-grade trash talk, corruption, get-rich-quick and disappointment. As I write, the one fight that could, on its own, keep boxing limping forward another year, between Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather Jr, has disintegrated into accusations of drug-taking and possible legal action. And to hell with the fans or the sport. While never exactly mainstream, boxing has spent years sliding out of the public’s affections.

“We’re avoiding boxing’s mistakes,” acknowledges Zelaznik. “We’re looking at the boxing blueprint and doing the exact opposite.” Hence the well-drilled press conference, the open arms and a brand so strong that fight-night sells out, no questions asked. “Fans know our fights are meaningful, important and exciting. Boxing has been about one-offs – one fight. We’re promoting a sport, a brand. So, we put 10, 11, 12 compelling fights on every card.”

The fighters know it, too. They are all under contract to UFC and the pay is spread more evenly from top to bottom. And there’s no room for trash.

“It’s odd, but it goes back to that martial arts base,” says Zelaznik. “[The fighters] respect each other. And you don’t have these big nasty entourages boxing has. Boxing is all about today. MMA is all about tomorrow – building something, and the fighters have that perspective.”

It’s working, too. Its pay-per view events beat out boxing and the cartoonish fakery of wrestling’s WWE, sometimes combined. UFC is shown in 36 countries and sells more merchandise than the Rolling Stones or Metallica. Now, even the mainstream American sports are threatened, despite the advantage of being on free-to-air TV. “In the 18-34-year-old demographic we rate better than anybody – we even beat the NFL sometimes,” says Zelaznik. “We’ve gone head-to-head against the NBA playoffs, the World Series – and beaten them.”

Dana White is near-obsessed with this mission. He wants it to be clean and true and real. He wants the mainstream – whatever that is. After that Brock Lesnar-Frank Mir fight, Lesnar carried on like the WWE grappler he once was – “disrespecting” his opponent, insulting the sponsor and his own employers. White simply wouldn’t stand for it. He gave Lesnar a hefty dressing-down in the change rooms and made the star apologise at a press conference. “You don’t have to act like something you’re not,” said White. “This isn’t the WWE. I don’t ask these guys to act crazy so we get more pay per views. That’s not the business I’m in.” Even more recently, local CFC fighter James TeHuna landed a late punch on an opponent, and posted a long letter of abject apology “deeply regretting the incident” and saying it was “contrary to the sport’s professional image”. Not screwing up.

“I think ‘mainstream’ means acceptance and with acceptance, inevitably, the money comes,” says Zelaznik. “It means understanding. When we go into new countries we have to answer questions about human cockfighting. Eventually those are going to go away, but we’re taking the punches now. There will be a fight in the UFC where the world will stop and watch. One day a fight will transcend.” He is probably right. Soon, names like Lesnar, St Pierre and heavyweight MMA’s unofficial world champion, Fedor Emelianenko, could be as known as Woods and Tyson – or Nathan Hindmarsh and Buddy Franklin.

Before the last fight at Luna Park’s Big Top, I step back out to the bar. On a small TV, screwed to the wall, the Eels and Rabbitohs are playing one of the most exciting NRL games of the season, and they are not being ignored. At least 25 blokes have given up their $130 fight privilege to stand in a draughty bar and watch league. As Andy Raymond, who calls Fox Sports’ CFC broadcast says, “MMA is still a maturing sport in Australia and has no choice but to play second fiddle to the big sports – the rugby leagues, the AFLs, the cricket. Australians love their football and anything is going to struggle against the football codes.”

In the UK, however, big UFC events there have had a strong effect on the local fight scene – more gyms, new organisations, more events, better fighters. Manchester’s Michael Bisping, almost unknown two years ago, comes to Australia as his city’s most-famous fighter after Ricky Hatton, and a tabloid favourite. And as 17,000 screaming fans at the ACER Arena will tell you, the next Aussie sporting superstar could be there at UFC 110, watching it all go down.

_________

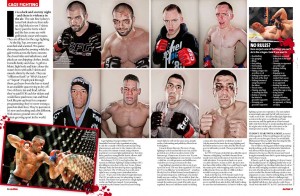

No rules? Here are just some of the things you can’t do in the octagon. Even if you want to

- Head-butting

- Eye gouging

- Biting

- Hair pulling

- Fish hooking

- Groin attacks

- Putting a finger into an orifice or cut

- Striking to the spine or the back of the head

- Striking downward using the point of the elbow

- Throat strikes

- Clawing, pinching or twisting the flesh

- Kicking or kneeing the head of a grounded opponent

- Stomping a grounded opponent

- Spiking an opponent to the mat on his head or neck

- Throwing an opponent out of the cage

- Holding clothing

- Spitting

- Engaging in an unsportsmanlike conduct that causes or intends an injury to an opponent

- Holding the wire or ropes or intentionally exiting the cage or ring

- Using abusive language (!)

- Timidity, including avoiding contact with an opponent, or faking an injury

_________

See a PDF of this: