Striking Distance

Striking Distance

When English footballing legend Robbie Fowler turned up to play football in semi-rural Australia, I went up to Queensland to talk to him. It was a bit of a mystery what he was doing there, even to himself, I think. He went on to play in Perth, then went back to the UK to get his coaching badges. This piece was for Alpha magazine. NB, the “God” I refer to in the opener refers to the nickname given to both Fowler and ex-AFL star Gary Ablett.

_________

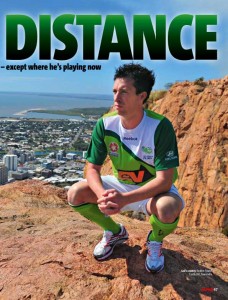

If there is a God, he lives in Melbourne, answers to Gary and keeps Himself to Himself. If there’s a God in far north Queensland, he wears protective headgear and goes by the name Thurston (as if that fools anyone). But now there’s another deity north of Brisbane: a foreign idol. Gods move in mysterious ways, but there are few moves as odd as Robbie Fowler to Townsville.

When Robbie Fowler, English soccer player, flew into town in January 2009, he would have been left with few illusions about the challenge he faced. Signs at the airport say, “Welcome to Cowboys country”. Taxi drivers think they’ve heard of him but they’re not sure. Either way, he doesn’t play rugby league, or they’d know all about it. Fowler can walk into any Townsville pub or shopping centre unrecognised. Take away air travel, just for a second, and the move looks even more remarkable. He is not in Liverpool any more. For a round-ball footballer, he could hardly have hidden himself in a more foreign environment on the planet. Understand this move, you think, and you might find the real Robbie Fowler.

Misunderstanding has plagued Fowler’s life. On arrival here, wooed by one of the A-League’s two brand-new teams for the 2009-10 season, it was assumed he’d have a quick look, go for a snorkel on the reef, maybe a local barbie or two, then hop on the next plane, never to return. North Queensland Fury? Admire their spunk and all that, but come on. Aussie Jade North was their other marquee prospect and that seemed a saner proposition. And besides, a day after Fowler did leave town, it started raining and didn’t stop until half the state was under water. No way would God return now. But he did.

_________

There have been two truly big names taking part in Australia’s football league: Dwight Yorke and Fowler. Yorke, a gifted good-time boy, whose new autobiography is a seemingly endless list of nightclubs and babes, lived here in a big Sydney apartment and played for the “glamour” club. To meet Fowler needs a trip to a small industrial estate outside Townsville, where the player is hanging around a corridor in a T-shirt and pants, in the Fury’s office units. It couldn’t be more low-key. Knowing the Fowler story – not nearly as wild as anything Yorke could offer – it’s almost surreal.

There have been two truly big names taking part in Australia’s football league: Dwight Yorke and Fowler. Yorke, a gifted good-time boy, whose new autobiography is a seemingly endless list of nightclubs and babes, lived here in a big Sydney apartment and played for the “glamour” club. To meet Fowler needs a trip to a small industrial estate outside Townsville, where the player is hanging around a corridor in a T-shirt and pants, in the Fury’s office units. It couldn’t be more low-key. Knowing the Fowler story – not nearly as wild as anything Yorke could offer – it’s almost surreal.

Robbie Fowler is the fourth-highest goal-scorer in the history of the English Premiership. In 1993, aged 18, Liverpool FC pushed pro forms under his nose, anxious to secure a player whose scoring exploits at youth level are still legendary. The local lad found himself a teenage millionaire and straight in the Liverpool first-team. He scored on his debut against Fulham in a Cup match. In the second leg, he scored five. A year later he claimed a hat-trick in 4½ minutes, still the fastest in Premiership history. For the next few years, the goals poured in. An avalanche of them. He got to 100 goals faster than any other Liverpool player. The fans gave him the nickname that could best express their adoration.

Primarily left-footed, but with a very useful right, Fowler is the best English finisher of his generation. He’ll find any way you want to get that ball in the net: thumps, nudges, headers, curlers, chips, blasters. “He often shoots early, doesn’t mind where he shoots from and seems to get late fade on his shots, like a golfer,” Mark Bosnich once said, after Fowler stuck three past his Aston Villa side. Almost uniquely, he could also generate power and swerve using very little back-lift, terrorising defenders with improvised strikes.

_________

THIS TENDENCY TO MAKE THINGS UP AS HE WENT ALONG, lethal on the pitch, could be catastrophic elsewhere. His prankster’s sense of humour made the men in suits wonder if Fowler’s mind was really on the job. Managers of the England national side, always scared of maverick talents, picked him for squads but never could quite trust him in the team. In a decade of top-flight football, 26 caps is a meagre haul.

“I can’t say they never picked me because of what they were reading or what people were saying. I don’t really know, to be honest,” Fowler says. “Whenever we used to go away with England, players would go in their room and relax. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to go out of my room and mix with the hotel staff. I didn’t want to look at four walls. So whether the manager thought, ‘He’s not concentrating on his job, he’s not got what it takes,’ I don’t know.” As his career went on, sadly, club managers often felt the same way.

The UK press liked the image of a wayward scamp, but Fowler helped them along. In 1999, as rival Everton fans goaded his alleged drug-taking, Fowler celebrated a goal by snorting the touchline in front of them. Typically, only afterwards did he think about the consequences. Other similar pranks sealed the image. Not far away, as Manchester United’s golden generation of Beckham, Scholes, Giggs, Neville and Butt won titles and cups, Liverpool’s Fowler, Steve McManaman, David James, Jamie Redknapp and Stan Collymore won almost nothing. Seen as gifted, fun loving and lightweight, they were dubbed “The Spice Boys”.

“It was a bit of a nightmare,” he admits. “I did go out and have a drink, but not as much as what people made out. And if I did go out, it would not affect my football. I would never do it one, two, three nights before a game. I was still always a footballer and did things by the book in terms of that. Maybe people see me out and think, ‘He’s out all the time.’ I don’t know. Our manager now, Ian Ferguson, says, ‘Listen, any player can go out, but if you do something stupid or it affects your football, then we’ll change the nights out.’ And it was the same back then.”

“It was a bit of a nightmare,” he admits. “I did go out and have a drink, but not as much as what people made out. And if I did go out, it would not affect my football. I would never do it one, two, three nights before a game. I was still always a footballer and did things by the book in terms of that. Maybe people see me out and think, ‘He’s out all the time.’ I don’t know. Our manager now, Ian Ferguson, says, ‘Listen, any player can go out, but if you do something stupid or it affects your football, then we’ll change the nights out.’ And it was the same back then.”

Perception is a strange thing. There are many broke, screwed-up, washed-up sportsmen, even in the wealth of the Premier League. But Robbie Fowler isn’t one of them. If you wanted to get all psychological, you might say there are two Robbie Fowlers in existence. One is the man sat in an office in Townsville. He is almost painfully downbeat. From a poor, close-knit background, he knows his family and mates back home won’t put up with a big mouth. He is the anti-Beckham. He’d probably rather die than launch an aftershave. At the height of his career he once said: “I am a naturally down-to-earth person. If ever I got big-headed my dad would put me down.” He treats interviews like he would signing footballs: a duty, but not what you’d call fun. Where better than Townsville to avoid all the fame nonsense and just play footy?

“When I first come here, I thought it was really, really quiet,” he says. “But the longer I was here, after a week, I found places that are livelier and where there’s more people. It grew on me a little bit more. But when I first went round town I didn’t have a clue where I was going. It was just typical me, going to the wrong places. I went home, had a good chat with the missus [about the move]. I’ve got four kids, you see, so we were really, ‘Is it worth it? Will the kids like it? Will I like it?’ It’s a massive decision. With the kids at school, as well.”

What finally swung the decision Australia’s way, as opposed to, say, the American league with Beckham, or super-rich Qatar, remains between Mr and Mrs Fowler. The reason he does give is a nicely tactful one. “It (Fury) was a new club, and I just felt it was really too good to miss. Hopefully this club will go on for many, many years, and now I’ve come here I’ll be part of the history of that club. Any country you go to, it’s rare that you’re finding a club starting up in the higher tiers of the league. It was a good choice to make.”

So far, so good, he says. They’ve got a place in Townsville and the three girls are mixing well in school (they also have a baby son). There are few signs that any of them are missing the bright lights or their community in Liverpool. “I’m quite a simple person, I like the easy things in life. I’m not flash or don’t go out of my way to get excited or carried away by anything. If it’s an easy life, then I’m all for that, and being here you can get into that. When I’m back in England, I don’t go for more than the occasional night out in London. I don’t go shopping at all the Bond St stores.

So far, so good, he says. They’ve got a place in Townsville and the three girls are mixing well in school (they also have a baby son). There are few signs that any of them are missing the bright lights or their community in Liverpool. “I’m quite a simple person, I like the easy things in life. I’m not flash or don’t go out of my way to get excited or carried away by anything. If it’s an easy life, then I’m all for that, and being here you can get into that. When I’m back in England, I don’t go for more than the occasional night out in London. I don’t go shopping at all the Bond St stores.

“Because I’m like that, I can adapt to anywhere. I’m quite grounded, as well. People can talk to me, I can talk to people. I’ll mix with anyone; I’m not big-headed and I’ll give people time. I’ll treat people the way they treat me; if they treat me nice then I’ll treat them nice.”

Living in a rugby league town is no problem, either. “When I came over people were saying that. But I’ve been recognised a bit more than I thought I would have done. That was a big surprise. It’s like being back in Liverpool: because I’m there all the time, people don’t bother me. They see me all the time – “there he is again” – you know. The mentality here is similar to that. They see me and don’t bother me. It’s brilliant, and you can get on with your life.”

_________

IN SOME WAYS IT’S A SHAME Fowler turned pro just as football in the UK truly went big-time. If he’d been born 20 years earlier, he could have had a laugh without any of the grief that now comes with it. “Since the football league became the Premier League, the scrutiny has magnified. You can’t even put into words how much it’s magnified. Footballers now are more like actors. They’re seen out and people want pictures with them. Years ago you’d get players who’d go to the game on the bus, smoking ciggies. Not a chance in hell that would happen now. The change has been phenomenal. I was probably one of the first [to experience it]. For me at the time it was hard to deal with. And I don’t mean that in a derogatory way. Suddenly I had people focusing on my life. Nowadays the young lads get media trained. I never did and players from my era never did.

“You don’t go into football to be famous; you just want to do well and be successful. And when you’re successful, the fame comes with that. But I just want to do well at football. I love football and if I weren’t being paid for it I’d still be playing it. I do a job that I love doing and if it weren’t a job I’d just be doing it with my mates.”

There is almost no trace here of the other Fowler: the prankster, who even now, rumour has it, has Fury players shuddering at the mention of his name and ice-baths in the same sentence. The sensible Fowler is also famous – for one thing: he is one of the richest footballers in the world. Drugs and nightclubs? Fowler put most of those Premiership pay packets in property. Lots of property. Fans have been known to sing, “We all live in a Robbie Fowler house” to the tune of Yellow Submarine. After more than a decade of mauling by the British press, Fowler is clearly still irritated by his flaky reputation, but he has definitely had the last laugh. “I’ve had people who looked after me unbelievably,” he says. “If you’ve got the right people around you, and you look after your money, it’s hard to screw up.”

Another thing that irritates him is being written off. Both the serious and the scamp Fowler have a love of football in common. He talks about his financial affairs as though they are part of a life that belongs some time in the future. For now, all he wants to do is play. “The fact is I’ve come over and there’s a few people who were saying, ‘Oh, he’s come over here on a holiday or his last pay day’ and I’ve proved them wrong. But fair play to these people who were saying that at the start, they’ve put their hand up and know they’ve made a mistake.”

After 2000-01, a season in which he and Liverpool won the League Cup, FA Cup and UEFA Cup, Fowler’s career meandered. Forced out of Liverpool by manager Gerard Houllier, he trailed from club to club, hampered by an ever more serious hip problem that eventually required surgery. Despite the goals, trophies and wealth, there remains the feeling in the UK that he has somehow failed; frittered his potential away. Fowler doesn’t dwell on this too much. For the first time in years he feels like the old Robbie. He may ache a bit sometimes and the searing pace is not what it was, but he is fit and scoring goals. And he is still only 34.

Those who wrote off Fowler when he arrived are probably very glad to admit their mistake. Watching him is a treat. At time of writing the Fury are bottom of the A-League and ravaged by injuries. But Fowler’s very presence adds thousands to every gate, home and away; he’s scoring high-quality goals; and his sheer enjoyment in every moment is obvious, no matter how many are watching. He loves it all. “It’s massive. When it’s the only thing you’ve ever done – and it brings you so much enjoyment, doesn’t it, football? Especially when you’re winning games, doing well and scoring goals, it’s just a brilliant feeling.”

To his own amazement, the teenage prankster now finds himself the oldest player in the side. “It seems like yesterday I was the youngest. That time seems to have flown by. It’s surreal.” He is the senior pro, wise old sage and all that. “The players here do look up to me, whether I like it or not, because of what I’ve achieved in my career. I was lucky enough to play with some great players and you pick up things.”

Whether he does like it or not, the A-League needs him and others like him, to pass on their skills and experience. And their enthusiasm. “I just love football. I’m playing in a new team with new players. At the end of the day we are all in the same boat and we all want to be successful for this side. Every player in every team wants to do well. There are players who mightn’t be blessed skilfully, but they’ll work hard and make up for it. And we’re all being paid for what we love doing. If I weren’t getting paid I’d still be doing it.”

We should pray for another season from Robbie Fowler, because, even in Cowboys country, they’ll be thanking God for small miracles.

_________

The EPL’s Top Five Goal-scorers

Alan Shearer

Goals: 260

Clubs: Southampton, Blackburn, Newcastle

Willpower and endless practice made him England’s deadliest striker for a decade, despite serious injuries.

Andy Cole

Goals: 187

Clubs: Newcastle, Manchester United, Blackburn, Fulham, Man City, Portsmouth…

The goal poacher scored at a ridiculous pace for Newcastle, then teamed up with Dwight Yorke at Man Utd.

Thierry Henry

Goals: 174

Clubs: Arsenal

Arsenal’s cutting edge of eight seasons matured from a streaky winger to a silky striker with awesome pace.

Robbie Fowler

Goals: 163

Clubs: Liverpool, Leeds Utd, Man City, Liverpool, Blackburn

In a career hindered by injury, Fowler was still a finisher supreme, while his all-round play was underrated.

Les Ferdinand

Goals: 149

Clubs: Queens Park Rangers, Newcastle, Tottenham, West Ham, Leicester, Bolton…

A big, popular, prolific and much-travelled frontman, Ferdinand’s strike-rate at QPR and Newcastle especially, were top-class.

_________

See this as a PDF: