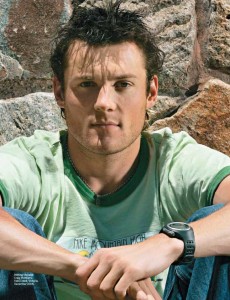

Craig Mottram

Craig Mottram

A straight Q&A with distance athlete Craig Mottram, from 2007, for Alpha magazine. A proper good athlete, Mottram has run some superb times, but had a catastrophic Beijing Olympics and has since disappeared from view. Where are you, Craig? Come back!

_________

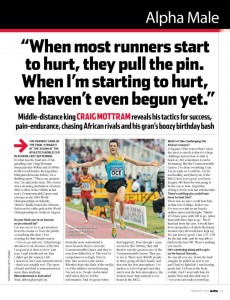

The moment came in the final straight of the 3000m at the athletics World Cup in Athens last September. In what was the final race of his gruelling year, Craig Mottram swept past the 5000m and 10,000m world record-holder, the legendary Ethiopian Kenenisa Bekele, for a thrilling upset. “This is my greatest win,” he said at the time. The victory was a stunning declaration of intent. After a silver in the 5000m at last year’s Commonwealth Games and a bronze at the 2005 World Championships at Helsinki, “Buster” finally bested the Africans. And now he’s after gold at the World Championships in Osaka in August.

Do you think you’re as famous as you should be?

I’m not one to try to get attention from the media or from the public or anything like that. I love running for that simple reason – I love to go and run. If that brings attention to me because of the fact I’m good at it, then so be it. Last year, I said it bothered me that I didn’t get the respect I felt I deserved, but I was misunderstood – that’s not actually true. The sport of track and field is misunderstood, more than anything.

Misunderstood in Australia?

Yeah, although people [in Australia now] understand it more because they’ve seen the Commonwealth Games and they’ve seen how difficult it is. The level of competition is so high. Prior to that, they weren’t quite aware. Whether that’s the fault of the media or of the athletes not performing, I’m not sure. People understand stuff when they’re fed the information. And it’s great [when that happens]. Even though I came second in [the 5000m], they still think it was the greatest race of the Commonwealth Games. They got to see it. There were 80,000 people in there going off their heads, and that was the best atmosphere. I’ve spoken to a lot of people and they said it was the best atmosphere, the loudest noise that anybody’s ever heard at the MCG.

What’s it like challenging the African runners?

What’s it like challenging the African runners?

A big part of the reason that I enjoy the sport so much is that it’s a huge challenge and we have to take it head-on. But sometimes it can be frustrating, like the Commonwealth Games. I’ve done everything I can, I’m as ready as I could be, I’m fit and healthy, and [then] one of the little f–kers is too good, you know (laughs). We knew he was going to be the one to beat, Augustine (Choge), but he just ran unbelievable.

There’s nothing you could have done to beat him?

There was no way I could beat him in that sort of shape. Believe me, I’ve run over this in my head a million times and thought, “Maybe if I’d have gone with 500 to go, rather than with three laps to go.” But if that had been the case, I would have been racing three of them (Kenyans), because they all would have kept up. He was just too good. I ran 3.57, 3.58 for the last mile, and he was able to [kick] in the last 200. There’s nothing you can do.

He’s cantering along with a grin on his face at the end…

He was all over me. Down the back straight, he pulled up next to me and I had no fight left. I was hurting pretty bad. I’d been at the front a while. And I went with him for maybe 50m and then that was it – you just can’t make yourself go any more. When I straightened up to do the home straight, he was well clear – it was over at that stage. My legs started to go and I couldn’t quite hold my form properly. I had to really concentrate on running through the line, because I knew every camera would be on me in that place, on my face to see what my reaction would be.

There’s no hiding place, is there?

There’s no hiding place, is there?

No. The track is very open; you’re on your own. People like to see the emotion of it, anyway – they like to see the raw emotion of what happens to people in those situations. But I was amazed when I came over the line and saw the time. I was sort of stunned, to be honest. I was a little bit disappointed not to win, but I was involved in probably one of the greatest races in Australian track and field history.

How do you feel about the Africans running in teams against you?

It’s a sign of respect; they know if it was one-on-one I’d be very hard to beat. The thing that’s difficult to deal with is they don’t really care which one of them it is. They all rotate turns pretty equally, and the strongest one, the one who’s feeling the best, will try to win the race. [But] that doesn’t bother me.

Do you get the impression that even though they look like they’re doing it easy, they’re actually hurting?

They hurt differently, though. When I start to get pretty tired, I breathe heavy and grunt and groan a little bit; those guys don’t make any noise, and they’re so light on their feet, you can’t even hear them. But you can tell that they’re getting tired. They don’t quite fit as close to you; they let you go past them easier – it lets you know that they’re hurting. When they’re done, that’s it; they don’t fight back. They don’t show it on their faces; they just keep going, but not at the same pace.

How do you go on despite the pain?

It’s what I’m training for. I kind of enjoy it, because I know I’m at the limits of what I’m supposed to be able to do. And then I think maybe I can take it that little bit further, and keep challenging myself. When most runners go out for a run and start to hurt, they think, “Ah, that’s it, pull the pin; I’ve done my exercise for the day.” But when I’m starting to hurt, we haven’t even begun the session yet. The session doesn’t start until you’re at that sustained punishment level. That’s when you start to get the benefit.

When did you realise you’d made it?

I always believed that I was going to make it. Most athletes that get medals at top championships always believe in themselves. In London in 2004, when I ran against Heile Gebrselassie and did 12.55, that was a fantastic race. My coach said, “Go after it, just follow Heile and if at any point in the last 600m you feel like you want to attack, just f–ing crush him, try and destroy him.” With 600 to go I was feeling really good, because I could see the finish line. I got a bit excited that I might run under 13 minutes and started thinking about that more than trying to win the race – and that probably cost me the win. That race moved me to the top three in the world that year on time. I’ve got it on my computer; I’ve watched it a million times. There’s a camera on us from the infield with 500 to go, and we were hammering. That was when I thought, “S–t, I can run. I’m actually good.” That was good, mate.

What are your goals?

To get better. I’ve got the World Championships in August, in Osaka, Japan. I got a bronze in the last one, and I want to go better. I honestly say that – a lot of people say it’s realistic. The race in Helsinki (in 2005) wasn’t perfect for me; there are areas in which I think I could improve and that’s what we’re training on every day.

What’s the most pain you’ve ever been in?

When we do hill reps, in training. They’re the ones I dread the most because they hurt for such a long time. We do three-minute hill reps and they’re uncomfortable from 30 seconds into them. There’s no respite from it – it’s just getting worse and worse and worse the whole way up. You’re really uncomfortable. I don’t feel much when I’m racing; there are so many factors going on, you’re completely in sync with your body – you know what’s happening but it doesn’t hurt. It’s more, “S–t, I’m starting to shut down now.” You run out of puff. That’s why you see people pulling faces – they’re trying to get more out of themselves, not because it’s hurting so bad. You’re trying to get yourself to go faster but you can’t because your body’s reacted the other way.

Who is your non-sporting hero?

My brother (Neil), who plays basketball. A few years ago he dislocated his knee and tore all the ligaments around it. It took him three years to get back from that, but he got back. To see him get back and see him win the NBL championship with Melbourne Tigers and then getting a Commonwealth Games gold medal was fantastic.

It was a good Commonwealth Games for the Mottrams, then?

Yes. My granny’s 80th birthday was on the Sunday after my 1500 final (on the Saturday night). The whole family had flown out from England. Neil was really happy because he got everything that he wanted and dreamt of, and I was disappointed and upset (Mottram fell over with 1½ laps remaining in the 1500m final in Melbourne) and had been drinking all day.

You got pissed?

I didn’t hit it too hard. I went out with a couple of mates. When I got back to my house, they were sitting there with a big slab of beer waiting for me. We tried to find something funny about it, although there wasn’t much. The next day my arse was on the front page of every paper in the country. It was a very strange time. I didn’t really know how to take it all. We went to my granny’s birthday and actually had a really good day. That helped me move on a little bit.

Tell us something about yourself that will surprise people.

I talk to myself. I mutter away, talking crap, singing a stupid song. And I’ve got a cat called Roy.

_________

See this as a PDF: