24 Hours in Griffith

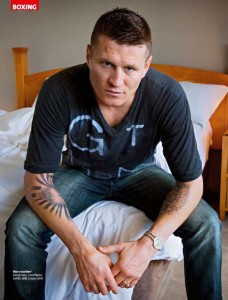

One of the most fun stories I ever did, as I accompanied boxers Danny Green and Roy Jones Jr on a bizarre promotional trip to small-town Australia. My cause was helped no end by the openness and cooperation of Green (who went on to win this fight). The photographer was Nick Cubbin and the piece was for Alpha magazine._________

The IBO cruiserweight champion of the world lunges forward and grabs me by the shoulder. “Mate!” he says. “You just missed it! There was a kangaroo in my room. It was looking at me and had little green boxing gloves around its neck.”

Boxing people, kids, mums and random others swarm the hotel corridor. Two of the kids are carrying a box. I’m still wondering if Danny Green has lost his mind when he tells the kids to bring back the box. “Look under that blanket, mate,” he says. “You’ll see.”

I lift up a corner and peek in. A tiny roo stares back at me. It sniffs my face. I think: when will this madness end? This Griffith madness.

_________

There’s no deader time at an airport than first thing in the morning. People slouch at departure gates, mentally still in bed, waiting to come back to life. Today, at Sydney Airport’s domestic terminal, these people include eight-time world boxing champion Roy Jones Jr. He looks like Cuba Gooding Jr, if Cuba Gooding Jr wore a silver tracksuit with white socks and sandals, looked knackered and needed about 12 sugars in his coffee.

There’s no deader time at an airport than first thing in the morning. People slouch at departure gates, mentally still in bed, waiting to come back to life. Today, at Sydney Airport’s domestic terminal, these people include eight-time world boxing champion Roy Jones Jr. He looks like Cuba Gooding Jr, if Cuba Gooding Jr wore a silver tracksuit with white socks and sandals, looked knackered and needed about 12 sugars in his coffee.

Jones is with his agent, a big Texan called McGee. “We’re goin’ to Griffith,” McGee confirms tiredly. “I don’t know what we’re doing there.” On the bus that will take us out to the plane, we wait, and wait some more. Someone is missing. Finally Danny Green jumps on, surrounded by boxing guys. They could only be boxing guys. Roy Jones stares silently out a window. Green cracks his neck and gazes out another. Green’s trainer Angelo Hyder stands between them, grinning like he knows the biggest secret in the world. And there we are: the next cruiserweight world title fight. All snug on a little bus. On its way to Griffith. Why bloody Griffith?

If you got in your car in Sydney and drove west, carefully observing the speed limits, for about eight hours, you would come to Griffith, NSW. An attractive rural city of less than 17,000 souls, not poor – one of the country’s wine and food bowls – a cosmopolitan immigrant population and a colourful past. Griffith has seen a fair bit, but nothing quite like what’s coming now.

The story of how Danny Green and Roy Jones Jr came to town changes with every telling, like many boxing stories. But the basic facts seem to be that local entrepreneur Rodney Prestia wanted to put on a night of boxing in town, like they used to in the old days. He knows Hyder and Hyder agreed to put two of his fighters, Adam and Steve Wills, on the card. And the Wills brothers are also mates of Danny Green. Months ago, Green agreed to come along and give the whole thing a boost. Then he signed to fight legend Jones on December 2 and things got complicated. The fight needed promoting and he and Roy Jones were going to be busy all over the country. But Green had that damn handshake agreement with Griffith. Screw it, he thought. We’ll all go.

The story of how Danny Green and Roy Jones Jr came to town changes with every telling, like many boxing stories. But the basic facts seem to be that local entrepreneur Rodney Prestia wanted to put on a night of boxing in town, like they used to in the old days. He knows Hyder and Hyder agreed to put two of his fighters, Adam and Steve Wills, on the card. And the Wills brothers are also mates of Danny Green. Months ago, Green agreed to come along and give the whole thing a boost. Then he signed to fight legend Jones on December 2 and things got complicated. The fight needed promoting and he and Roy Jones were going to be busy all over the country. But Green had that damn handshake agreement with Griffith. Screw it, he thought. We’ll all go.

At the plane, a member of the ground staff puts his fists up in front of his face as the bus door opens. The aircraft fills up with boxers and agents and journalists and trainers and one lady concentrating very hard on her book. I see the back of Jones’s neat, cropped head two rows forward. He has small ears. He scratches the head with a scarred hand about the size of the bucket on a dragline. Shit, though. Roy Jones Jr. It’s like having Madonna sat in your lounge.

_________

If you were to list the top 20 boxers, any weight, from the past 100 years, Roy Jones Jr would probably make it in. He’s a locked in hall-of-famer, a giant of sport. Fighting most of the time at middleweight, he once went for the heavyweight crown and won. In the 1990s, he played a high-grade basketball match for the Jacksonville Barracudas in the morning, before his fight in the evening. More people have swiped their Visa card for a Jones fight on HBO than for all but three or four stars. If you wanted to throw around figures, you’d say he got $15 million for his last outing. But now he’s 40. Now he’s facing Australia’s Danny Green. And right now he’s on a plane. To Griffith.

Griffith airport is bedlam. A bloke bellows, “F—king hell, it’s Roy Jones.” Posed photos are taken; fists are raised. Jones puts on a grin. He seems thin under his tracksuit. People boil everywhere, shouting. Bags lie on the ground. TV cameras point. A Ferrari 360 is parked bang out the front. Green wakes up. Promoter Prestia tells him to get in. Soon Green is gone. Jones is gone. We are what’s left behind.

Griffith airport is bedlam. A bloke bellows, “F—king hell, it’s Roy Jones.” Posed photos are taken; fists are raised. Jones puts on a grin. He seems thin under his tracksuit. People boil everywhere, shouting. Bags lie on the ground. TV cameras point. A Ferrari 360 is parked bang out the front. Green wakes up. Promoter Prestia tells him to get in. Soon Green is gone. Jones is gone. We are what’s left behind.

_________

All that energy and nowhere to put it. Boxing blow-ins, all biceps and black T-shirts, walk up and down Griffith’s main drag in ones and twos. Up, then back, then up again. In the lobby of Green’s hotel the champ is telling a receptionist how hard the rumba is, charming her. “Ah, yeah,” she says, “Ah, yeah.”

He sees me. “Mate, I’ve got to get breakfast. Can I talk to you later?” He practically runs out to his Ferrari and sits in it, gunning the engine blissfully. When he’s had enough of that he peels a U-turn and accelerates off. For six seconds. He finds a spot by the cafe, parks and gets out. All that energy and nowhere to put it.

When I catch him up he is being interviewed for the telly. A man shouts, “Green machine!” from a passing car, and waves a fist in the air. Green grins and waves back. Kids hang about with deep interest. Folk do delighted double takes. Nemesis Anthony Mundine cleverly fill arenas with those keen to see his head taken off, but this is the payback. Green loves people. Loves them. And everyone loves him back. Down the street come 20 postie bikes.

Twenty postie bikes are coming down the street. On the other side are 10 more. They sure do get a lot of mail around here. I see more and more postie bikes, little Hondas, putt-putting. Am I dreaming? I have to know. Two posties have parked. Are you posties? I ask. They are not. This is the annual postie bike challenge, of course. Every year they ride from Brisbane to Melbourne, 400km per day. Via Griffith. On postie bikes. Uh-huh.

Sometime later, the phone rings in Green’s hotel suite. He bounds over and yanks up the receiver. “South-West Steel. Tony Speaking.” There is a long pause as the person at the other end digests this rubbish. Life with Green can be unpredictable. Baby kangaroos get released into hotel rooms; he tells a story about a running egg-fight outside a posh hotel. When Roy Jones Jr stepped out of his first Sydney press conference, he found Green and Hyder had nicked his limo. Green made the baffled driver tell Jones that Bernard Hopkins (Jones’s proposed opponent after Green) said thanks for the lift. One day in early 2008, Danny Green, a boxer in the prime of his career, rang up Hyder and told him he’d retired. Hyder said he was mental anyway and that was that.

Sometime later, the phone rings in Green’s hotel suite. He bounds over and yanks up the receiver. “South-West Steel. Tony Speaking.” There is a long pause as the person at the other end digests this rubbish. Life with Green can be unpredictable. Baby kangaroos get released into hotel rooms; he tells a story about a running egg-fight outside a posh hotel. When Roy Jones Jr stepped out of his first Sydney press conference, he found Green and Hyder had nicked his limo. Green made the baffled driver tell Jones that Bernard Hopkins (Jones’s proposed opponent after Green) said thanks for the lift. One day in early 2008, Danny Green, a boxer in the prime of his career, rang up Hyder and told him he’d retired. Hyder said he was mental anyway and that was that.

It’s an all or nothing life, and now that Green has figured out how much he really loves boxing, he is back and busting out of his skin to fight Roy Jones Jr. “People can’t believe it’s actually happening. They still didn’t believe it until Jones was actually in the country. People astound me with their doubts. I wouldn’t go on telly unless it was actually on. It’s real, mate. It’s real.”

Even he seems slightly puzzled now by the decision that halted his career (“a gut feeling. An instinctive thing”). “I love doing what I’m doing, and the adrenaline and excitement of taking on someone like Roy Jones – the reward is huge. I don’t care about his achievements, his ability, who he is. My job is to take down the legend. That’s what I relish, mate. I love that shit.”

Occasionally, when he’s going full barrel like this, you get a hint of the other Danny Green. The one that climbs through the ropes and comes for you without mercy. “I turn into a monster,” he acknowledges. “I want to destroy my opponent. I want to knock him out. I don’t want to win on points. I don’t want to defeat Roy Jones in a classic enthralling boxing match, I want to knock the bloke out.”

Odd, isn’t it? I say. All of us, here, in Griffith. “It was pretty difficult getting Jones here,” he admits. “I had to convince him it was worthwhile coming. But he’s pretty professional about the whole thing.”

And they still haven’t spoken to each other since the first press conference in Sydney a week before. It’s like travelling with a big dysfunctional family. Almost Famous with boxing gloves. And we all know it’ll end in a fight. “It’s not strange to me, mate,” says Green. “If I felt strange, I would be overawed. But I’m not overawed one bit. I respect Roy Jones, but I don’t care about the bloke. And being around him more is good because it desensitises me to his legendary status.”

There is a lunch event at Westend winery. Details are sketchy. “I dunno what’s happening, mate,” says Green, buttoning up a loud red shirt. “I’m just going with the flow.”

_________

Green rumbles right up to Westend’s front door in the Ferrari. There are cheers and applause. The place is straining at the seams. For your $150 Fight Night ticket they also threw in lunch and the chance to meet Green and Jones. People take photos of Green, of the Ferrari, of each other.

Inside, Jones has been literally cornered by reporters. Still in his tracksuit, he sits quietly on a stool. When the first question is asked he comes alive. His head jerks back and forth. He wags his finger. He talks fighting and respect and knockouts. He works it, baby.

The main bar area is crammed with punters holding phones and cameras. Tables groan with food or gloves and T-shirts for sale. The two boxers are introduced one at a time through double doors, like it’s their own fight night already. Shouted at by the MC from a distance of an inch, Jones gives a good interview. He promises to “put on a good show for y’all” and talks about the size of the fight in the dog. Like Mike Tyson, his voice is surprisingly soft and slightly lisping. Sometimes he speaks about “Roy Jones” as if that Roy Jones was somewhere else entirely.

Green’s entrance pumps a huge cheer through the room. His game face is on. He can do this stuff, too. The interviewer hollers at him; Green says his style “isn’t rocket science”. He mentions respect, but says, “On December 2, someone’s going to get knocked out.” More cheers.

Later, Jones pushes past me before I’ve even realised it’s him. Strange. He has no presence at all; a ghost in a shell suit. He can turn it off and on like a lamp. The American spends an hour pinned at the back of a sunny courtyard by a line of people toting merchandise to sign. Two huge, sweating security guards flank him, communications cords spiralling into their ears. Inside, Green sits at his own table in that violent red shirt, signing, signing. Posed photos. Fists raised. The grab and grin. Again and again.

_________

In the Griffith Indoor Sports Centre at 4.30pm, Angelo Hyder tears up tape and hangs it on a ring rope. Danny Green, in black boots, long black pants and a black T-shirt, takes the tape and straps his hands into fists. The microphones are in his face. He talks happily, endlessly. He is still high on the kangaroo prank his gang played on him.

Across the airy arena, past the heavy bags and speed bags, kids, mums and dads sit in plastic chairs for the public training session. Green tells them he’s going to show a little of what he does. He builds from stretching and callisthenics, pops briefly but with precise skill at a punchball, then strips to the waist.

Two months out from the fight, neither he nor Jones have begun serious training. Green looks fit but not yet ripped. As the kids watch, rapt, Green stalks Hyder around the ring, cutting off corners, whistling combinations into the pads. There is no reverse gear in this man’s psyche. Hyder mutters, corrects, orders, advises. By round four we know we’re in the presence of a world-class warrior. Battering combinations set up gigantic left hooks and uppercuts; Hyder covers up with both pads together as Green assaults him with natural power. The really big ones land with a loud, explosive grunt.

For the first time I think properly about the fight. Jones is a casual favourite, but he knows what he’s in for. Green may not be using rocket science, but he’s been around a very big block, in a rough neighbourhood. He can take it and he can dish it out. If he lands one of those Sunday specials on Jones’s chin, Jones will wake up next month.

All the kids run over and scramble into the ring for photos. Green puts the littlest one on his sweating shoulders. It’s been a grinding couple of weeks on the road, but he looks like he’s just climbed a mountain and found gold on the top.

_________

Just out of town is Griffith’s big old Yoogali Club. The car park is full by 7pm. Griffith’s finest are out, dressed for the fighting. Reception is jammed. The same sweating security men revolve in the melee. Are those things in their ears connected to anything? Posters on the walls show Green and Jones, and shout, “Griffith’s biggest sporting coup ever”. Lads in their best gear head to the bar for jugs of Carlton. Bearded Bandidos zip dark jackets over their tummies. Some of the ladies here have never seen a professional punch thrown. Tonight, it doesn’t matter. This is where it’s at.

In the arena lights hang from the ceiling in nets. The walk-up tickets are fenced away from the $150 VIP dinner tables with red tape. More than 1000 locals are in. Roy Jones is announced like he’s actually fighting instead of just eating dinner. A standing ovation. The Juuuun in Junior goes on for whole seconds. He’s shed the tracky dacks for jeans and a shirt.

Two young amateurs hustle around the ring, slipping punches nervously in the dead atmosphere of early evening. Showing their skills in front of boxing royalty. At the end Jones climbs into the ring to present the winner’s trophy.

The night warms up. Fighters come to the lights in clouds of dry ice and music, and do their best for an increasingly noisy crowd. The sponsors get a healthy airing every time, to keep the meter fed. Roy Jones is called away from his schnitzel and presents the trophy and sits back down and climbs back into the ring and presents another trophy and sits back down again. The MC says his name over and over, as if he’s afraid the man will just vanish if he doesn’t.

Danny Green appears, leading young aboriginal fighter Nigel Goolagong to the ring, and the cheers bounce off the ceilings and everyone mutters “Green” and “Jones”, but still the two men will not look at each other. I corner Jones briefly at his table tucked near the ring and tell him he’s considerably out of his territory here. He stares me directly in the face and says, “I’m never out of my territory. The only territory is God’s territory, and he’s everywhere. Everything belongs to the Lord.”

Righto. You serious about this Green fight, then?

“Yeah, dead serious. He’s a hard-punching dude. He can take me out with one punch, I know. I got to count on lady luck and knock him out.” He says he loves small towns. This is what he knows. In small towns you know everything about everybody. The good things and the bad.

Before the main bout, an actual title fight between welterweights Steve Wills and Thai Sataporn Singwancha, Jones clambers into the ring again, only this time Green is there too. The MC stirs it up. Everyone agrees that December 2 will feature a knockout. Jones shows his bicep; Green looks grim. The delirious crowd eat it up like ice-cream. This is a Big Deal. Right here in Griffith.

Steve “The Serial Killer” Wills has Angelo Hyder and Danny Green in his corner and too much for his gangly opponent. Midway through round two he finds Singwancha’s chin with a whopping straight left and the Thai sits on his bottom. The towel flies in. Wills is still WBO Asia Pacific champion. Fight night ends. Somewhere an afterparty gets going.

After 24 hours in Griffith the first flight out does not feature the current IBO cruiserweight champion from Perth or the eight-time world champion from America. The roadshow has disintegrated. In the cold early morning of the departure lounge, exhausted Bandidos hunch over their hangovers, jackets zipped all the way up.

_________

One night, a few days after Griffith, when Roy Jones Jr is safely back in Pensacola, Florida, in his own gym and his own bed again, Danny Green rings me up. Something is bothering him. “Mate,” he says, as I hunt for a pen. “One of the main reasons I came back after I retired. It was the fans. I don’t think I made it clear. Their support is what I love. It’s what keeps me doing it, keeps me going on. It’s one of the great things about what I do.”

I believe him. I remind him of the chaos at Griffith airport; the kids in the high street and the sports centre; the scrum at the winery; the crowd at fight night. There’s no faking that, from either side. Green sounds relieved. He hangs up.

_________

See a PDF of this: