Scaling Down

Scaling Down

A fun day fooling about west of Sydney; the fun doesn’t seem to have translated into the piece so much, although it’s efficient, at least. Written for Alpha magazine, in about 2007.

________

These days, when every other kid is throwing himself down a mountain in a giant washing-up tub filled with bowling balls or something, abseiling is distinctly old-school. Abseiling is what “extreme” dudes used to do before someone realised it really wasn’t as scary as all that.

Abseiling never went away; it just became part of the furniture and learning to abseil is your passport to more fun stuff, stuff like canyoning. The fact is, to get down into – and through – most canyons, even a moderate one like today’s, you’ve got to abseil, and it doesn’t take long to learn.

On a trial run down a three-metre practice rock, we’re put in leather harnesses and helmets and taught that, provided the ropes are anchored into the rock well enough, the biggest danger on an abseil is putting a finger in the descender and chewing it up. Or going upside-down. Even roped up, I look over the side of a 30m cliff, with a further 40m drop-off into the valley below, and my brain’s going, “No, no, no, no.”

I’m attached to the descender, given my braking line and unclipped from the short safety rope anchoring me to the cliff-top. Next, I have to step backwards, lean far out over the edge and take a step off. Again, I’m thinking, “No, no, no. Stop, stop, stop.” Once the step is taken, things calm down a bit and I can start stiff-legging my way down the cliff face. Until, in this case, I run out of cliff.

No-one has told me about this part. The first three metres are just overhang; suddenly I find myself swinging free in space, sat in a giant leather nappy. I swing round so I’m looking out over miles of valley. It is a short, surreal moment. I actually shout, “Help,” mainly because all my brain can give me is, “I bloody told you.”

A voice from below shouts, “Keep coming down,” which seems like a good idea. I pay out the line through the descender and, more or less in control, descend stylishly into a small tree.

________

So much for abseiling. After lunch our group of 12 and two guides enter the canyon. Some canyons you can raft into, many harder ones need at least one abseil before you reach the creek at the bottom. This one, Empress Canyon, in Sydney’s Blue Mountains is of “moderate” difficulty, which means a long set of steps (and as the guide says, water flows downhill, so the hardest part of the whole day could be the long climb back out again).

We’re going to be wet for most of the afternoon, so we get into wetsuits, while all our gear goes into packs that will double as handy flotation devices. We’re ready. But what for?

Let’s be honest: canyoning is messing about in a river; the kind of thing you did as a kid. It’s not potholing and it isn’t caving: at this level it isn’t deep, dark or nasty. There’s a whiff of danger, but only enough to keep you on your toes. What you are doing is running is running along a creek getting really wet and having fun all day.

We set off along the creek, wading only about knee-high, despite recent rains. The water is 12C, but gets much colder in winter, so canyoning is really only a summer activity. Within two minutes we are leaping a two-metre drop into a deep rockpool and backstroking to the other side. It’s the first of several jumps, slides and swims: all part of nature’s obstacle course.

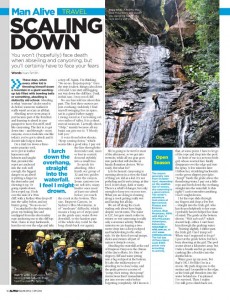

Abseiling the waterfall at the end of Empress Canyon is the climax of the day’s efforts. It’s 30m of slippery cliff and water jetting into a big rockpool at the bottom. It’s also the trickiest piece of abseiling we’ve done today, and the guide gives us a series of “jump, then swing, then jump” instructions that I immediately put into reverse order before forgetting completely. All I know is that, at some point, I have to let go of the rope and drop into the pool.

In front of me is a nervous Irish girl, whose worried face finally disappears over the edge and into the spray. A few minutes later I follow her, stumbling backwards on the green slippery precipice. “Jump” bawls the guide above the thundering water. I pay out a little rope and lurch down the overhang, straight into the waterfall. Is this right. I can’t remember anything. I feel I might drown.

I let the rope slide through my fingers and drop a few feet – straight into the Irish girl, who has frozen helplessly to her rope. I probably haven’t helped her state of mind. The guide at the bottom shouts, “Wah, wah-wah!” which doesn’t help, either. I can’t hear him through the rushing water.

Twisting slightly, I slither past the Irish girl. Can I jump yet? When was I supposed to let go? I peer at the guide below, but he’s busy shouting at the girl. The pool seems about a kilometre away, but I take a breath and let go anyway, crashing like a boulder into the depths below.

Water goes up my nose, but that’s OK. I feel like I’m in a movie. My pack drags me to the surface and I scramble to the edge, as the Irish girl thunders into the water behind me. I’m pleased I’ve survived. Then I realise I’ve still got to climb back out.

________

See this as a higher-res PDF: